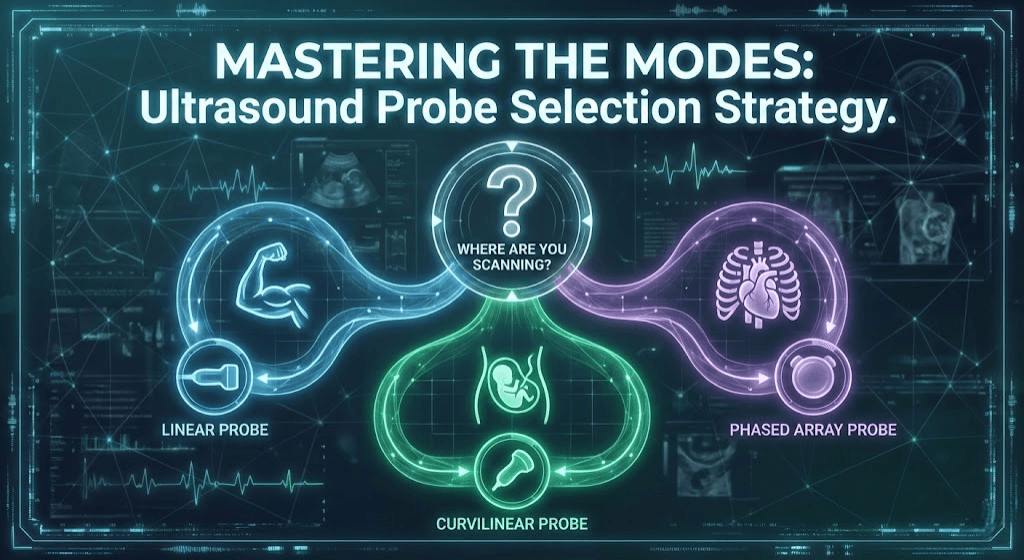

Ultrasound Transducer Technology: A Technical Comparison of Linear, Curvilinear, and Phased Array Probes

In the field of diagnostic medical sonography, the transducer—or probe—is the interface between the imaging system and the patient. It is the most critical component for determining image quality, resolution, and depth of penetration. Selecting the appropriate transducer is not merely a matter of preference but a decision rooted in the physics of sound waves and anatomical requirements.

Understanding the distinct characteristics of Linear, Curvilinear (Convex), and Phased Array probes is essential for any clinician performing point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS) or comprehensive diagnostic exams. Each probe type utilizes a specific arrangement of piezoelectric crystals and operates within defined frequency ranges to optimize imaging for specific body habitus and tissue types. This article provides a professional technical comparison of these three fundamental transducer types.

The Linear Probe: High Frequency and Superficial Precision

The linear array transducer is characterized by the flat arrangement of its piezoelectric crystals. In this configuration, the crystals are aligned in a straight line, producing sound waves that travel parallel to one another. This beam geometry results in a rectangular field of view, where the width of the image near the probe surface is identical to the width at the bottom of the screen.

Linear probes typically operate at high frequencies, usually ranging from 5 MHz to 15 MHz, though specialized probes can reach much higher frequencies. In ultrasound physics, frequency is inversely proportional to wavelength and penetration depth. Consequently, the high frequency of the linear probe offers superior axial and lateral resolution but is limited by significant attenuation as the sound waves travel deeper into tissue.

Due to these physical properties, linear probes are the gold standard for imaging superficial structures. The high resolution allows for the distinct visualization of fine details, such as nerve fascicles or the intima-media thickness of arteries. However, the utility of this probe diminishes rapidly beyond a depth of 6 to 8 centimeters.

Primary Clinical Applications

- Vascular Imaging: Ideal for visualizing the carotid arteries, jugular veins, and peripheral vasculature for DVT studies or vascular access procedures.

- Musculoskeletal (MSK): Essential for assessing tendons, ligaments, and muscles, allowing for the diagnosis of tears or inflammation in superficial joints like the wrist or ankle.

- Small Parts: The standard choice for imaging the thyroid gland, testicles, and breast tissue.

- Ocular Ultrasound: Used for measuring optic nerve sheath diameter, provided the power output is regulated appropriately.

The Curvilinear (Convex) Probe: Depth and Field of View

The curvilinear probe, also known as the convex array transducer, features crystals arranged along a curved surface (an arc). This physical curvature causes the ultrasound beam to fan out as it travels away from the probe face. The resulting image is sector-shaped or pie-shaped, with a field of view that widens significantly at greater depths.

Curvilinear probes generally operate at lower frequencies, typically between 2 MHz and 5 MHz. According to the principles of acoustic physics, lower frequency sound waves have longer wavelengths, which are less susceptible to attenuation by soft tissue. This allows the beam to penetrate deep into the body, reaching depths of 20 to 30 centimeters depending on the patient's body habitus.

The trade-off for this deep penetration is a reduction in image resolution. Because the scan lines diverge as they go deeper, the lateral resolution decreases at greater depths compared to the near field. Despite this, the curvilinear probe is indispensable for general abdominal imaging where visualizing large organs and deep structures is prioritized over microscopic surface detail.

Primary Clinical Applications

- Abdominal Imaging: The primary choice for evaluating the liver, gallbladder, kidneys, spleen, and pancreas.

- Obstetrics and Gynecology: Used for transabdominal fetal assessment and pelvic organ evaluation due to its wide field of view.

- FAST Exams: A critical component in trauma protocols (Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma) to detect free fluid in the peritoneum.

- Lung Imaging: Useful for detecting pleural effusions and consolidation in the deeper lung fields.

The Phased Array Probe: Beam Steering and Cardiac Dynamics

The phased array transducer is technically distinct from linear and curvilinear probes in its method of beam formation. While it has a flat footprint, the crystals are grouped tightly together in a small square or rectangle. Rather than firing crystals in a simple sequence, the system uses phased timing delays to fire the crystals.

This electronic "phasing" allows the ultrasound beam to be steered and focused without moving the probe physically. The beam emerges from a single point and fans out, creating a triangular or slice-of-pie image shape. The footprint of a phased array probe is very small, which is a deliberate design choice to allow imaging through narrow acoustic windows.

Phased array probes typically operate in a low-to-medium frequency range (1 MHz to 5 MHz). While they offer deep penetration similar to curvilinear probes, their primary advantage lies in temporal resolution. They are capable of high frame rates, which is essential for imaging moving structures, such as the beating heart.

Primary Clinical Applications

- Echocardiography: The small footprint fits perfectly between the intercostal spaces (ribs) to image the heart without bone shadowing.

- Transcranial Doppler: Capable of penetrating the thin temporal bone to assess cerebral blood flow.

- Abdominal Imaging (Alternative): Can be used for abdominal scans when access is limited, though the field of view in the near field is very narrow.

Comparative Analysis: Selecting the Right Tool

Choosing between these transducers requires a clear understanding of the "Resolution vs. Penetration" trade-off. There is no single probe that can perform all examinations with equal efficacy. The clinician must match the physics of the probe to the anatomy of the patient.

Linear vs. Curvilinear

The distinction here is primarily between superficial resolution and deep penetration. If the target structure is within 4 centimeters of the skin surface, the linear probe is superior due to its high frequency and parallel beam structure. Conversely, if the target is an organ like the kidney or liver in an adult patient, the linear probe's signal will attenuate before returning a usable image. The curvilinear probe sacrifices surface detail for the ability to visualize the entire abdominal cavity.

Curvilinear vs. Phased Array

Both of these probes offer deep penetration, but their footprints and beam shapes serve different purposes. The curvilinear probe has a large footprint, which can be difficult to maintain contact with on a patient with narrow rib spaces. The phased array excels here, as its small footprint allows it to peer between ribs. However, the curvilinear probe offers a much wider field of view in the near field, making it better suited for scanning large static organs, whereas the phased array is optimized for the high temporal resolution needed in cardiac assessment.

Conclusion

Mastery of diagnostic ultrasound begins with the appropriate selection of hardware. The linear probe offers precision for superficial structures, the curvilinear probe provides the depth required for abdominal assessment, and the phased array probe delivers the access and temporal resolution necessary for cardiac imaging. By understanding the underlying physics and beam geometry of each transducer, clinicians can maximize diagnostic accuracy and optimize patient care.

Related Articles

Common Technical Faults in Medical Ultrasound Systems: A Comprehensive Analysis

An in-depth professional analysis of the most frequent hardware and software failures in medical ultrasound machines, ranging from transducer damage to power supply instability and user interface malfunctions.

Mastering the Philips X7-2t TEE Probe: Common Faults, Diagnostics, and Repair Solutions

A comprehensive guide to troubleshooting and maintaining the advanced Philips X7-2t xMatrix TEE probe, covering mechanical failures, electronic diagnostics, and professional repair protocols.

In-Depth Analysis: Common Causes of Power Supply Failures in Medical Ultrasound Systems

A comprehensive technical guide exploring why ultrasound power supply units fail, illustrated with specific case studies from GE and Philips systems, and outlining essential diagnostic and preventive strategies.